| Pre-Design Study

Designing for Belonging

A Qualitative Investigation Into Digital Inclusion for Blind & Low-Vision Users

| Overview

This study explored how blind and low-vision (BLV) adults define and experience digital inclusion and exclusion, what barriers persist, and implications for future designers. We conducted four semi-structured interviews and a qualitative analysis in order to discover how inclusion and exclusion manifests in lived experiences beyond standard compliance checklists.

The main contributions established in this research are through: (1) a user-centered definition of digital inclusion based on lived experience; (2) qualitative research demonstrating that accessibility barriers persist despite implemented accessibility standards; and (3) design implications that place emphasis on early BLV user involvement and development informed by the lived experiences of BLV users.

Role

UX Researcher

Affiliation

DePaul University, Jarvis College of Computing and Digital Media

Areas

Accessibility, Design, Research

The Problem

To address the inaccessibility to digital spaces for blind and low vision (BLV) users, accessibility standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) established expectations for inclusive digital content [11]. Accessible design not only enhances satisfaction among users with disabilities, but improves user experience for everyone, and drives business success [2,9]. Consequently, leading digital products are frequently espoused as accessible and inclusive [9].

A large-scale survey conducted in 2024 by WebAIM found that 96% of those using assistive technologies, such as screen readers, encounter daily accessibility barriers [10].

Usability metrics tell only part of the larger story of digital accessibility. Shinohara & Tenenberg found that social and emotional factors have a substantial influence on how and whether users engage with digital experiences and assistive technologies [3].

BLV users routinely rely on workarounds to overcome barriers, leading many efforts to focus on identifying barriers and implementing fixes. However, research from Reyes-Cruz et al. argues that these approaches focused on barriers may overlook the competencies and practices that BLV users rely on [1].

Research Questions

Our study addresses the following research questions:

How do adults with blindness or low vision describe digital inclusion, and what makes them feel included or excluded online?

What frustrations and barriers do they experience when using websites or applications that claim to be accessible?

What opportunities exist for designers to create more inclusive digital experiences that reflect user’s needs, emotions, and identities?

Methods

| Participants

Four BLV adult participants who regularly use assistive technology to navigate digital spaces were recruited with the assistance of Dr. Oliver Alonzo. All interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom.

| Data Collection

Four semi-structured interviews (20–40 minutes)

Audio & Transcription Recording with Consent

| Data Analysis

Individual Inductive Coding

Collaborative Coding

Affinity Diagramming

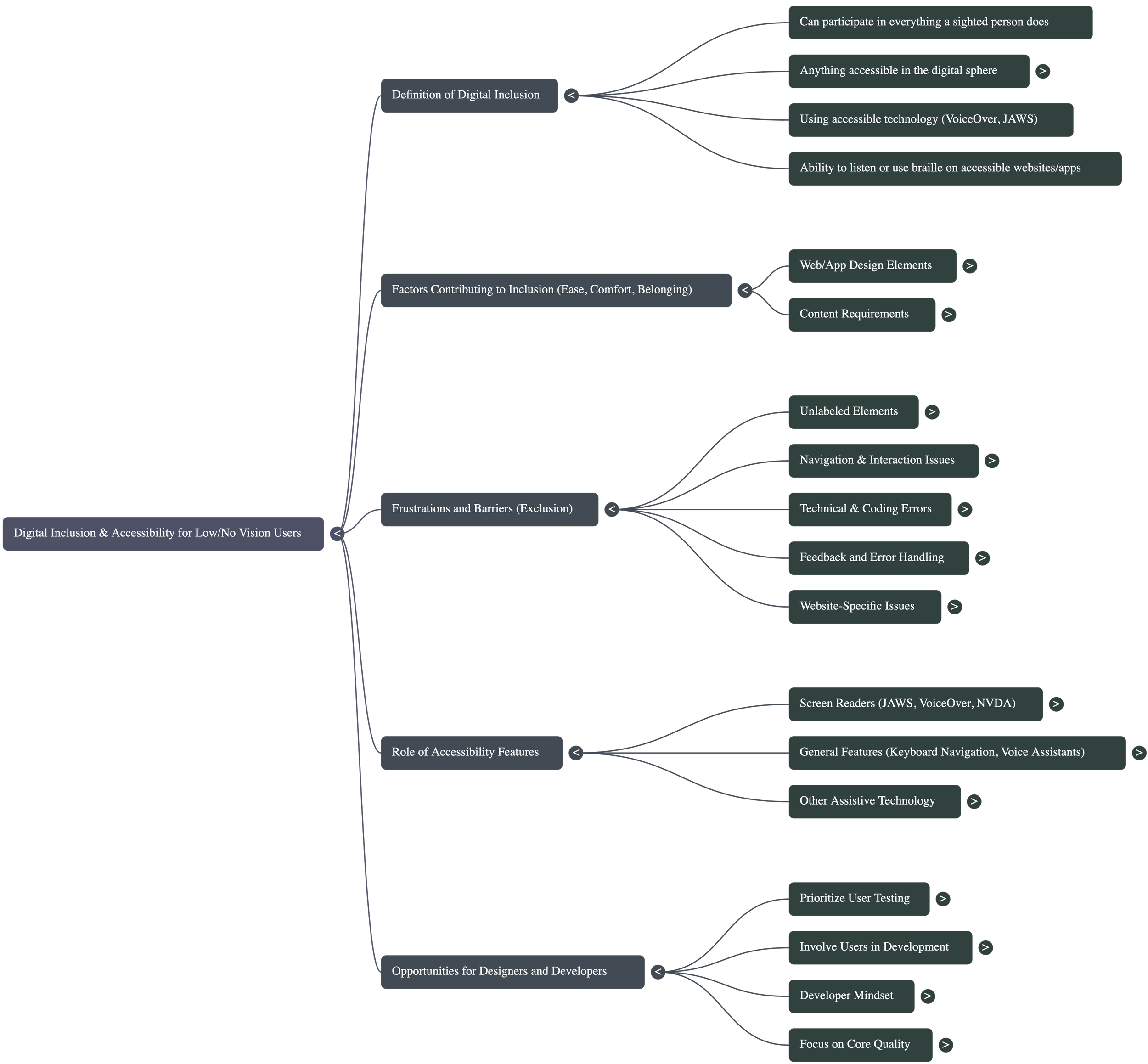

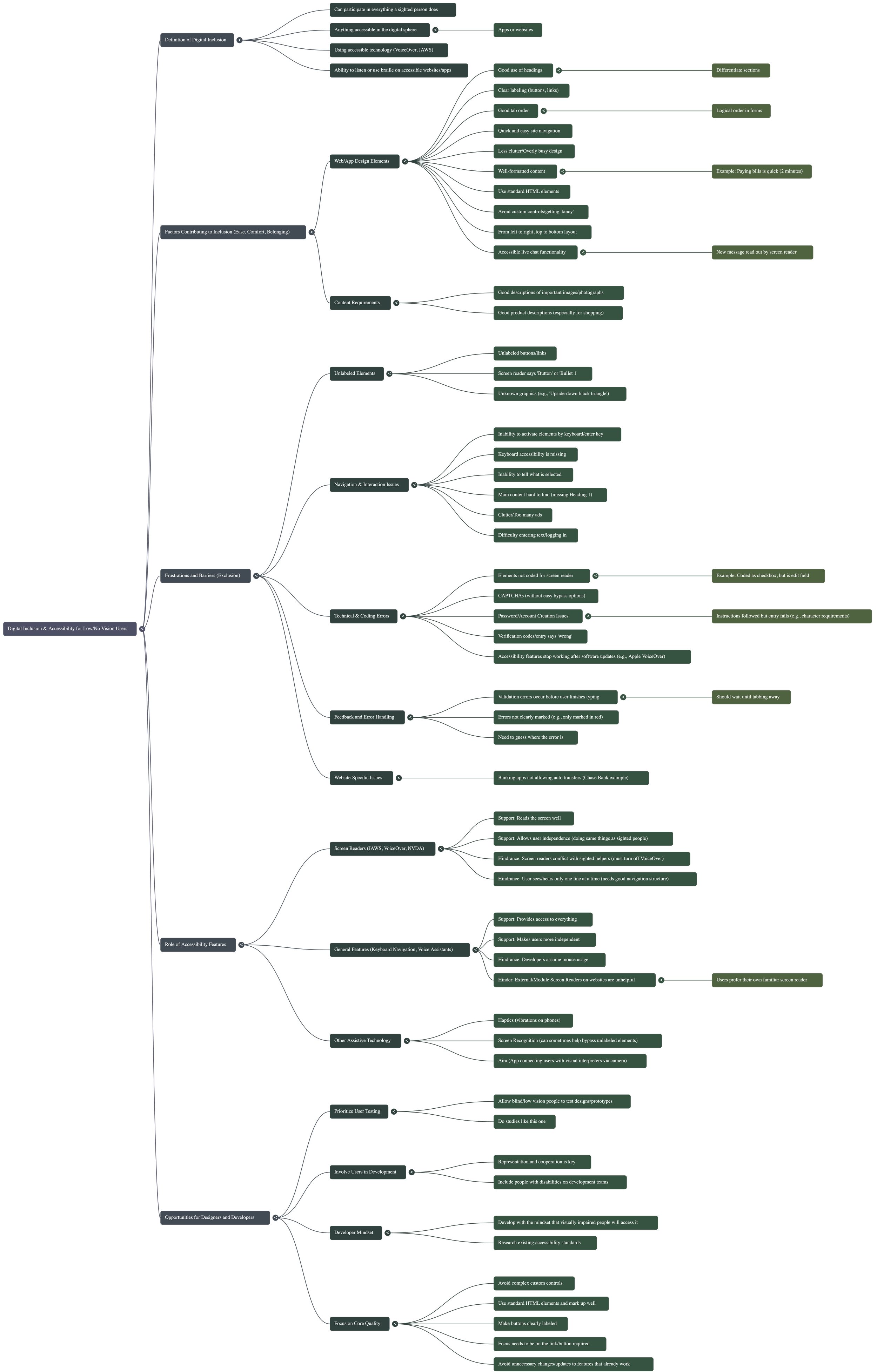

Mind-Mapping and data synthesis utilizing NotebookLM

Key Findings

| How do adults with blindness or low vision describe digital inclusion, and what makes them feel included or excluded online?

Participants described digital inclusion as being able to participate in digital life with the same independence and ease as sighted users.

They explained that inclusion means completing everyday tasks like reading emails, sending messages and accessing documents without extra steps or workarounds.

Participants shared that they do not want novel specialized or complex tools. Instead, they want websites, apps, and assistive technologies that already exist to function together properly.

One participant summarized inclusion clearly: “I just want to use the website like anyone else.”

| What frustrations and barriers do they experience when using websites or applications that claim to be accessible?

Participants explain that assistive technology only works well when the website or app itself is built correctly.

When it isn’t, they are forced into unnecessary struggles with products that often claim to be accessible. Participants relied on community and sighted peers to develop workarounds.

Common issues included:

Cluttered layouts and poor content structure, CAPTCHAs without alternative means of human verification, and errors without details that obstruct form submissions.

Validation errors appear too early while typing. Participant #1: “It says ‘invalid entry’ when I’m still typing.”

Error messages shown only in color, making them impossible to detect visually. Participant #1: “Don’t just mark it in red, I can’t see that.”

Password rules being followed correctly but still rejected. Participant #4: “I put in the password exactly like it says… it keeps saying it’s wrong.”

| What opportunities exist for designers to create more inclusive digital experiences that reflect user’s needs, emotions, and identities?

Participants reinforced the need for the direct involvement of BLV users in design and testing. Participants felt many accessibility barriers persist due to developers making assumptions without testing the product with blind or low-vision users.

Participant #2 explained: “They obey all the formal rules, but they don’t test with anybody who actually uses it. Enough of us would love to volunteer our time.”

Participant #4 emphasized the same point: “Bring people with different disabilities on the development team.”

Participants strongly believe that early and continuous involvement of BLV users, rather than late-stage testing, would prevent many of the barriers they face.

| Opportunities Expressed by participants:

Simplifying cluttered layouts

Including BLV users early in design

Providing non-visual alternatives for CAPTCHAs

Avoiding color-only indicators

Improving password and form validation

Hiring or collaborating with people with disabilities

| Supplemental Findings

Participants reported that small issues often create the biggest barriers, such as unlabelled buttons, confusing layouts, inaccessible forms, and unexpected pop-ups that slowed down tasks and increased frustration.

Participants appreciated when websites had clear structure, predictable layouts, properly labelled inputs, and descriptive alt text. These features allowed assistive tools to work correctly and made digital tasks simpler.

Participants felt motivated when digital tools worked consistently and allowed them to complete tasks independently. Reliability played a key role in their trust and confidence.

Some participants shared that they relied on community resources, online groups, peers with similar experiences, and online services that specialize in assisting BLV users. These spaces helped them discover workarounds when accessibility failed.

Implications

| Our findings suggest several important implications for designers:

Integrate BLV users early and consistently in the design and testing process rather than waiting until the final stages.

Treat BLV users as co‑designers or collaborators, not only testers of finished products, to ensure meaningful change.

Prioritize structural clarity and predictable layouts since these patterns make digital environments easier to navigate and support assistive technologies reliably.

Avoid color‑only indicators, unclear validation messages, and inaccessible CAPTCHA formats, as these introduce unnecessary barriers and force users into workarounds.

These implications complement existing guidance on accessibility policy and process by emphasizing lived experience and continuous user involvement.

References

1. Gisela Reyes-Cruz, Joel E. Fischer, and Stuart Reeves. 2020. Reframing Disability as Competency: Unpacking Everyday Technology Practices of People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376767

2. Jonathan Lazar, Daniel F. Goldstein, and Anne S. Taylor. 2015. Ensuring Digital Accessibility Through Process and Policy. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283676880_Ensuring_Digital_Accessibility_through_Process_and_Policy

3. Kristen Shinohara and Josh Tenenberg. 2009. A Blind Person’s Interactions with Technology. Communications of the ACM 52, 8 (August 2009), 58–66. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/1536616.1536636.

4. M. Al-Razgan, R. Alotaibi, and A. Ahmad. 2021. A Systematic Literature Review on the Usability of Mobile Applications for Visually Impaired Users. PeerJ Computer Science 7 (2021), e771. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.771

5. Oussama Metatla, Alison Oldfield, Taimur Ahmed, Antonis Vafeas, and Sunny Miglani. 2019. Voice User Interfaces in Schools: Co-designing for Inclusion with Visually-Impaired and Sighted Pupils. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, Paper 378, 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300608

6. Scott Hollier. 2017. Technology, Education and Access: A “Fair Go” for People with Disabilities. In Proceedings of the 14th International Web for All Conference (W4A ’17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, Article 33, 1–2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3058555.3058557

7. Shaun K. Kane, Meredith R. Morris, Annuska Z. Perkins, Daniel Wigdor, Richard E. Ladner, and Jacob O. Wobbrock. 2011. Access overlays: improving non-visual access to large touch screens for blind users. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST ’11). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, 273–282. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/2047196.2047232

8. Shaun K. Kane, Meredith Ringel Morris, and Jacob O. Wobbrock. 2017. Access overlays and inclusive technology design: Research with blind users. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025590

9. Simon Waller, Mark Bradley, Ian Hosking, and P. John Clarkson. 2015. Making the Case for Inclusive Design. Applied Ergonomics 46, Part B (January 2015), 297–305. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.012

10. WebAIM. 2024. Screen Reader User Survey #10: Results. Retrieved from https://webaim.org/projects/screenreadersurvey10/

11. World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). 2023. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2. Retrieved from https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG22/